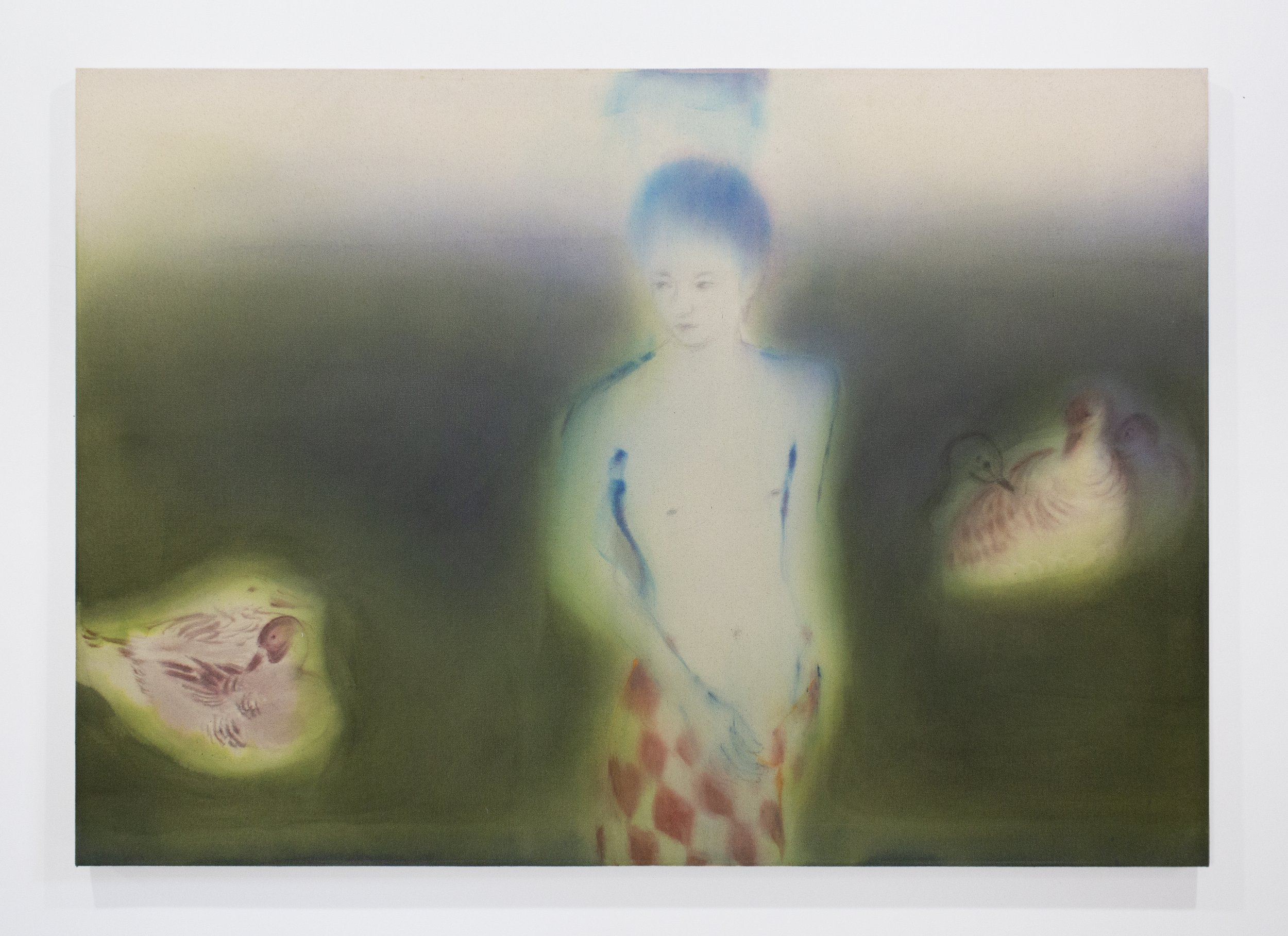

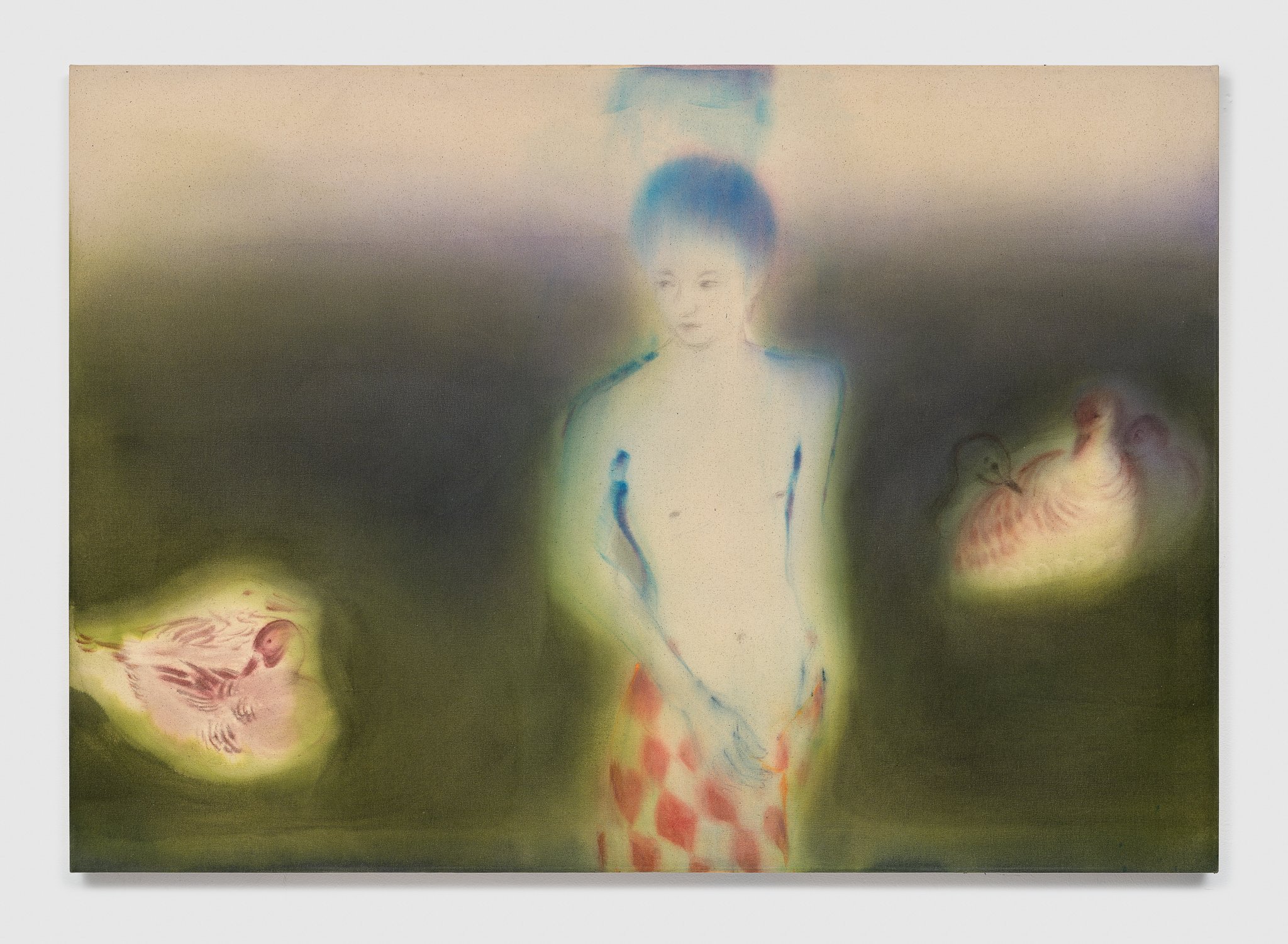

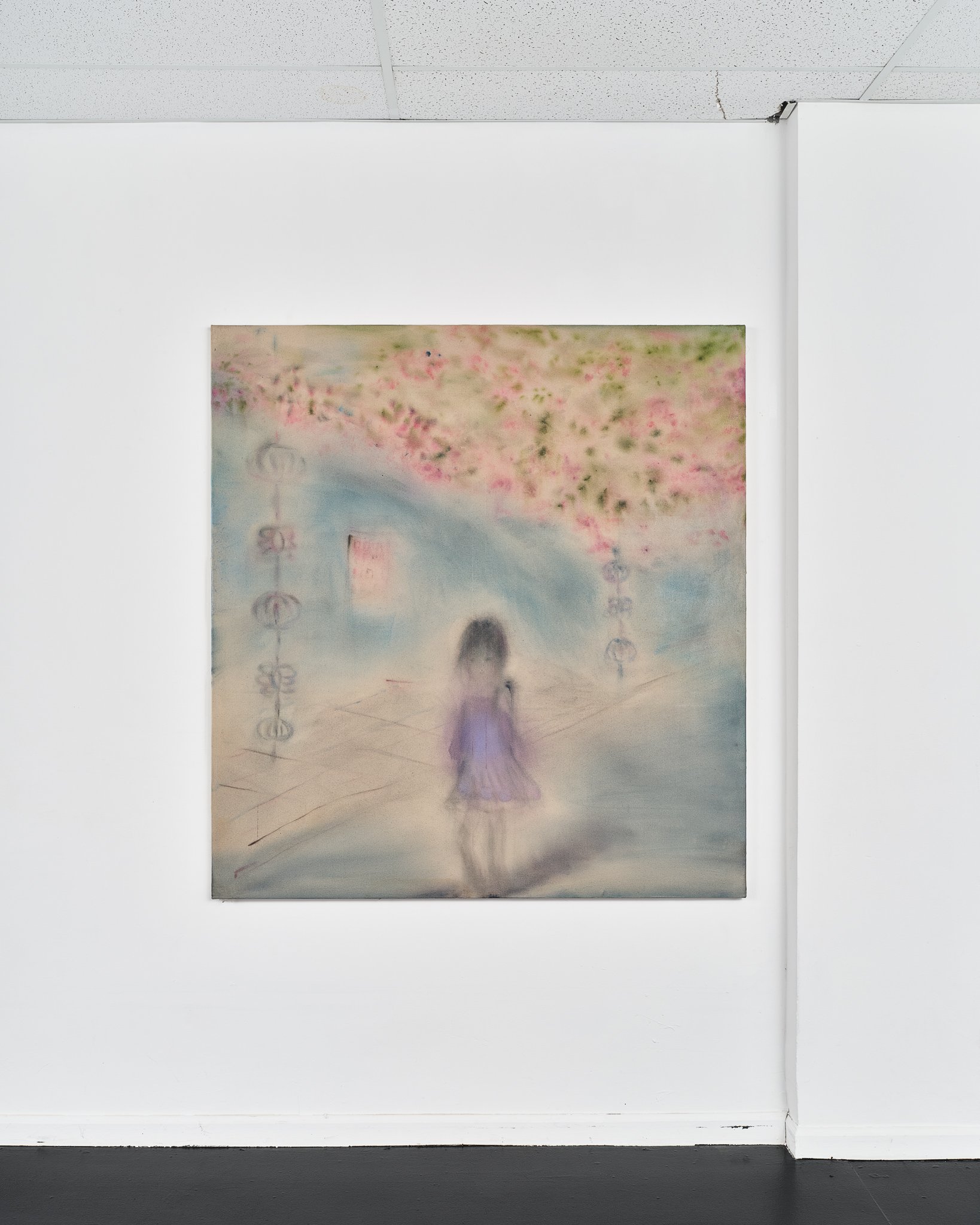

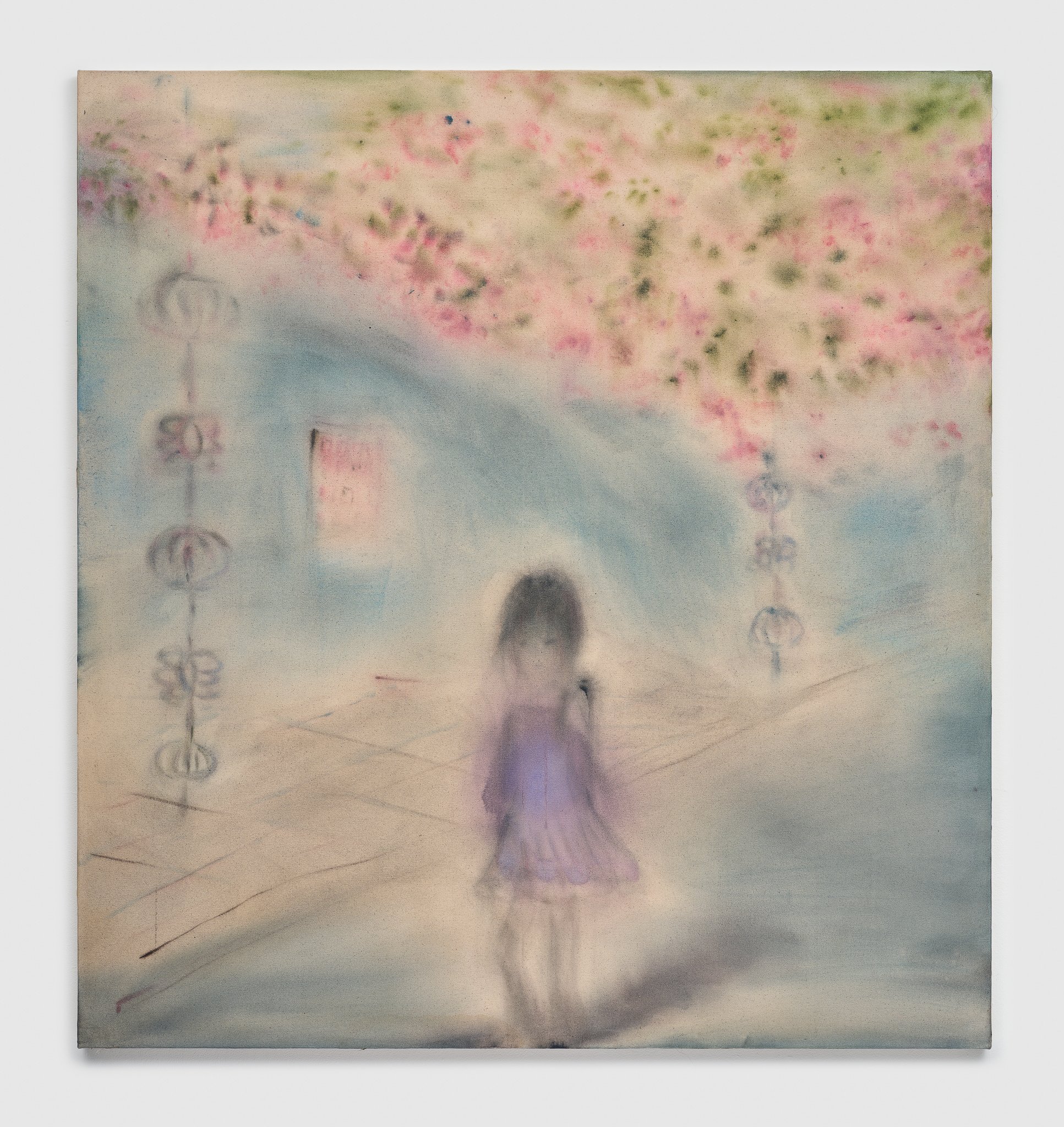

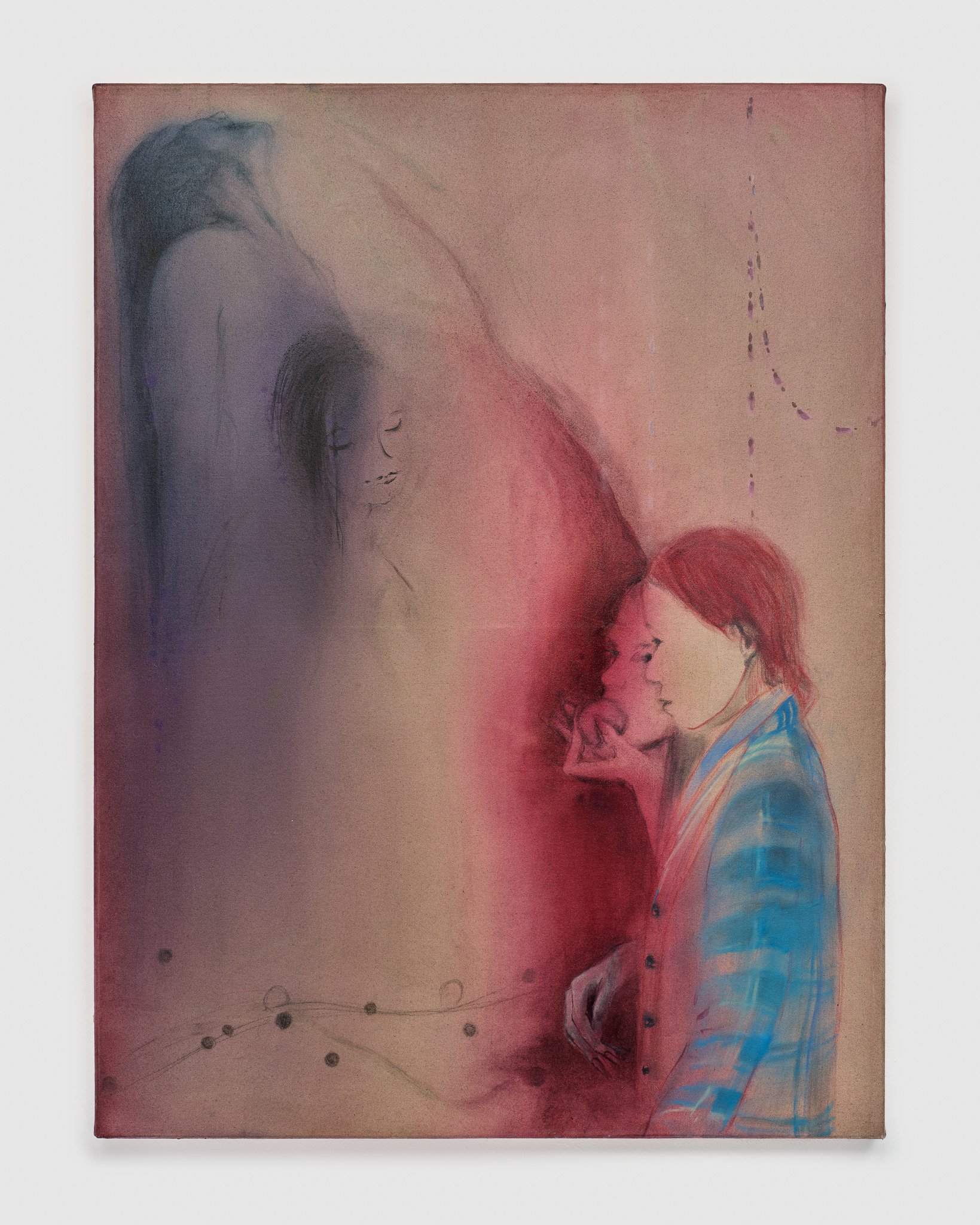

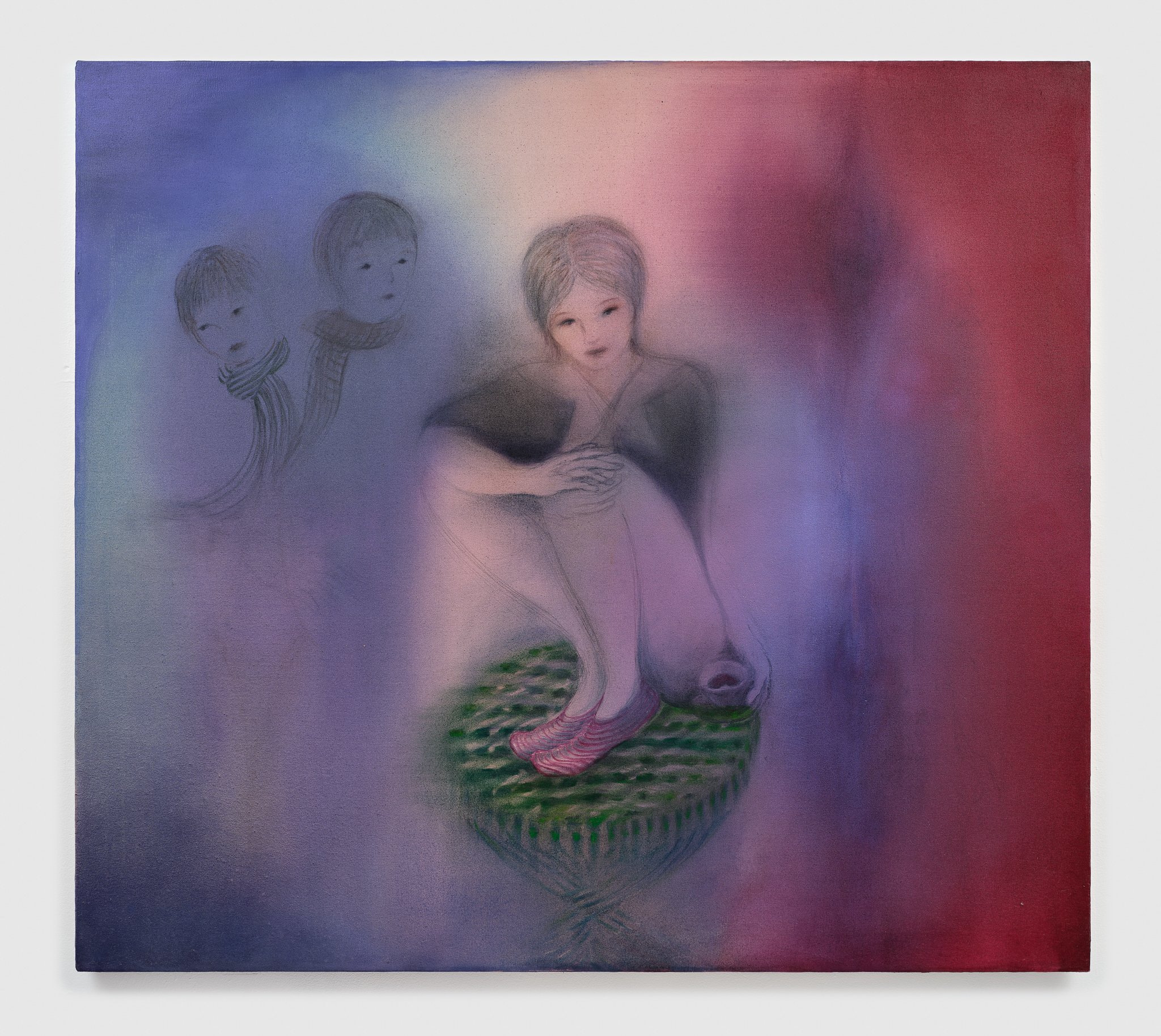

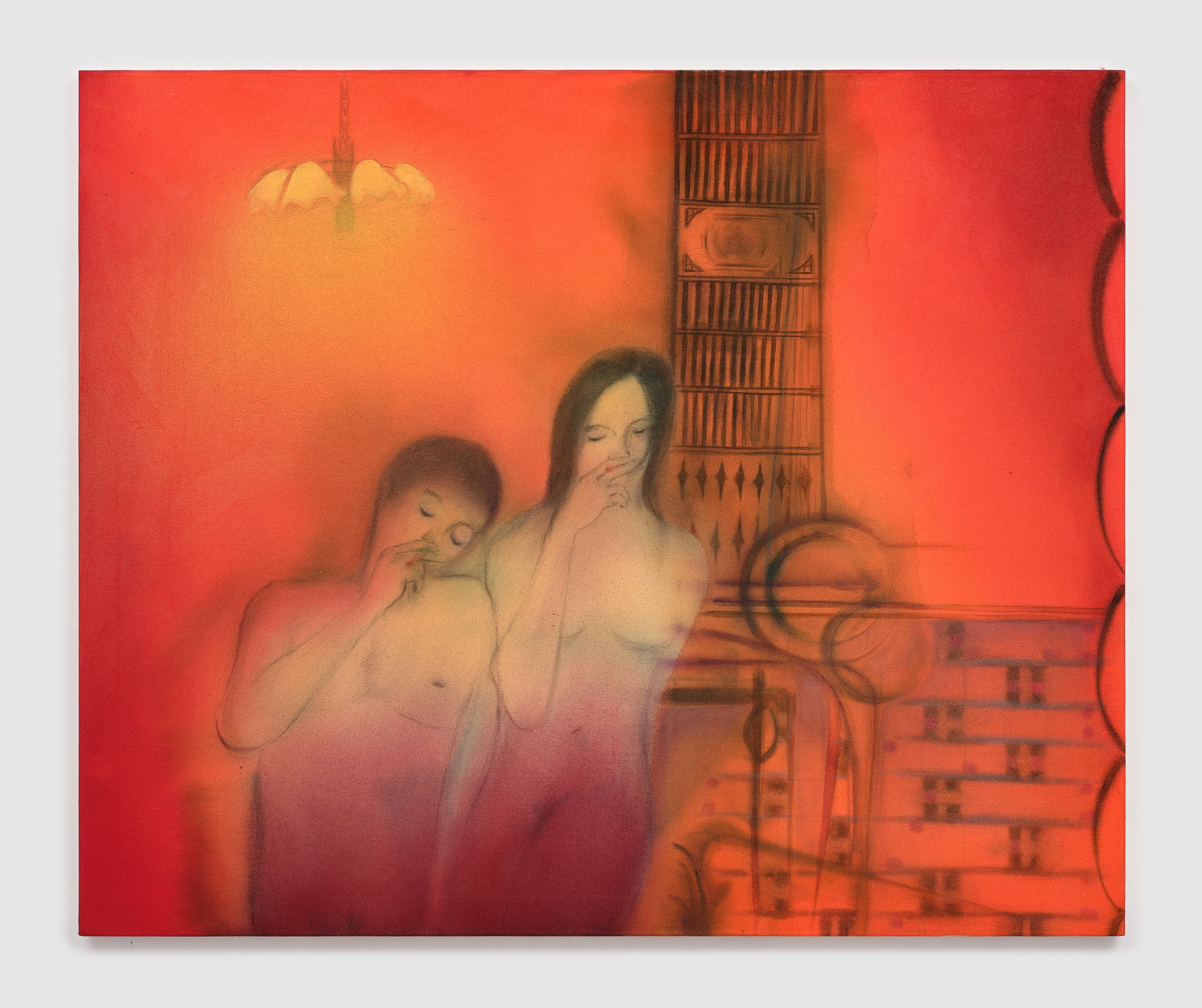

Xingzi Gu

Pure Heart Hall

April 27, 2024–July 13, 2024

Reception: Saturday April 27, 6–8pm

Press

Artforum: Critics’ Picks: Xingzi Gu at Lubov

W Magazine: Xingzi Gu’s Dreamy Paintings Explore the Dark Side of Coming of Age

Interview Magazine: How Japanese Coming-of-Age Films Influenced Painter Xingzi Gu’s New Show

Hyperallergic: Xingzi Gu’s Dreamlike Portraits of Youth

Elephant Magazine: Xingzi Gu’s Echoes of Erotica

snapSHOT of the art world: Xingzi Gu at Lubov

Hyperallergic: Where Carnal Needs Meet Unearthly Setting

Galerie Magazine: 8 Must-See Solo Gallery Shows Around the Country in June

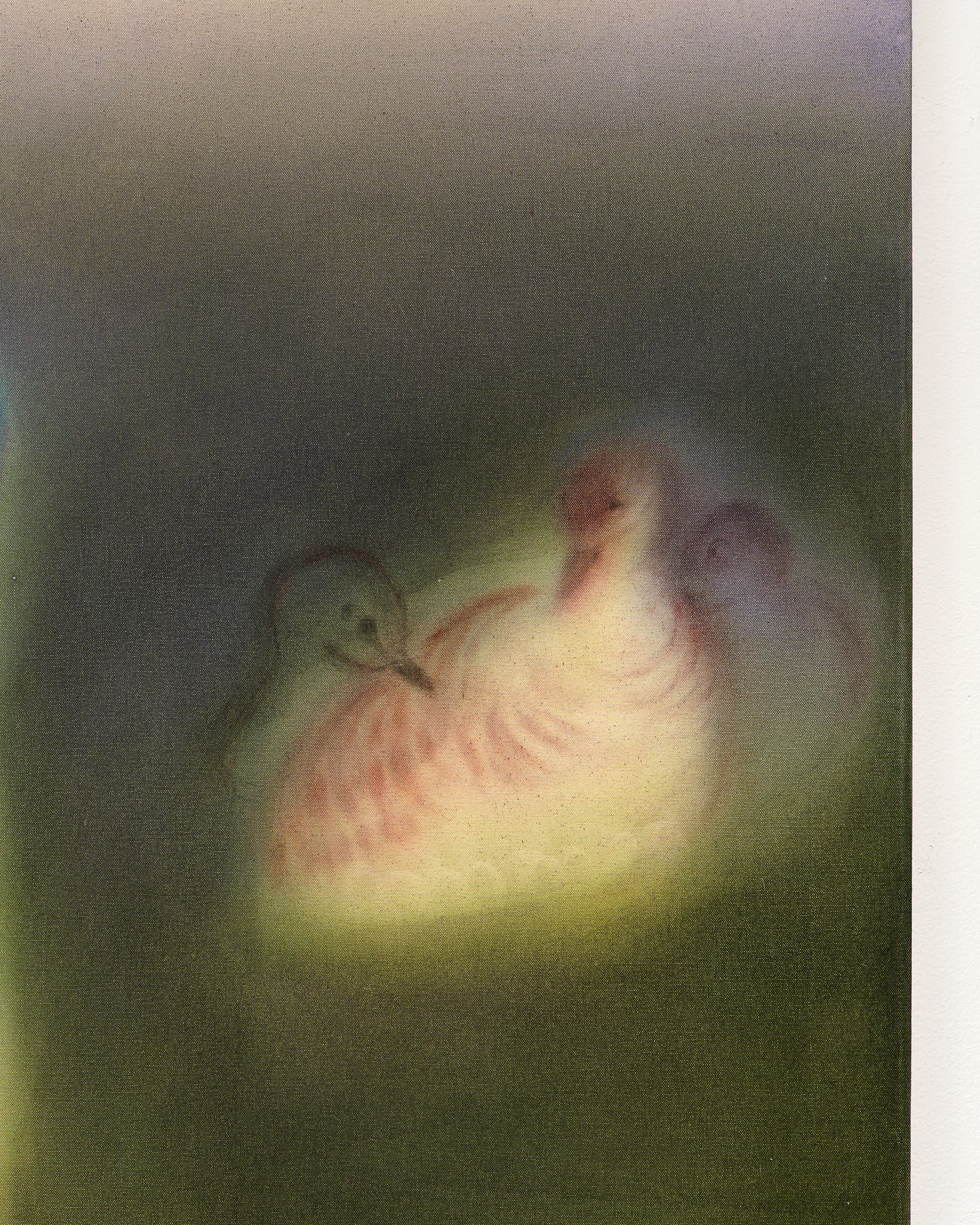

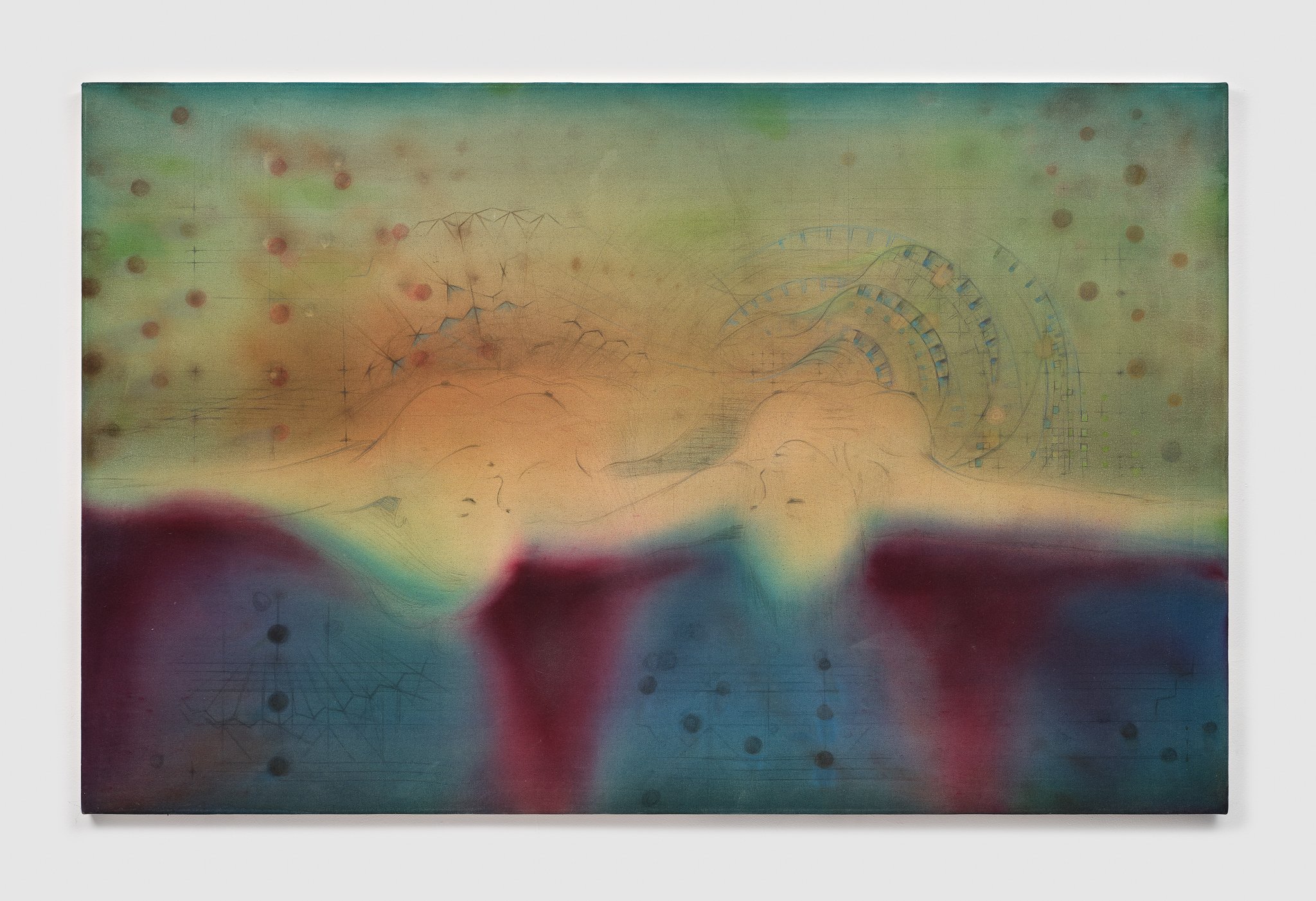

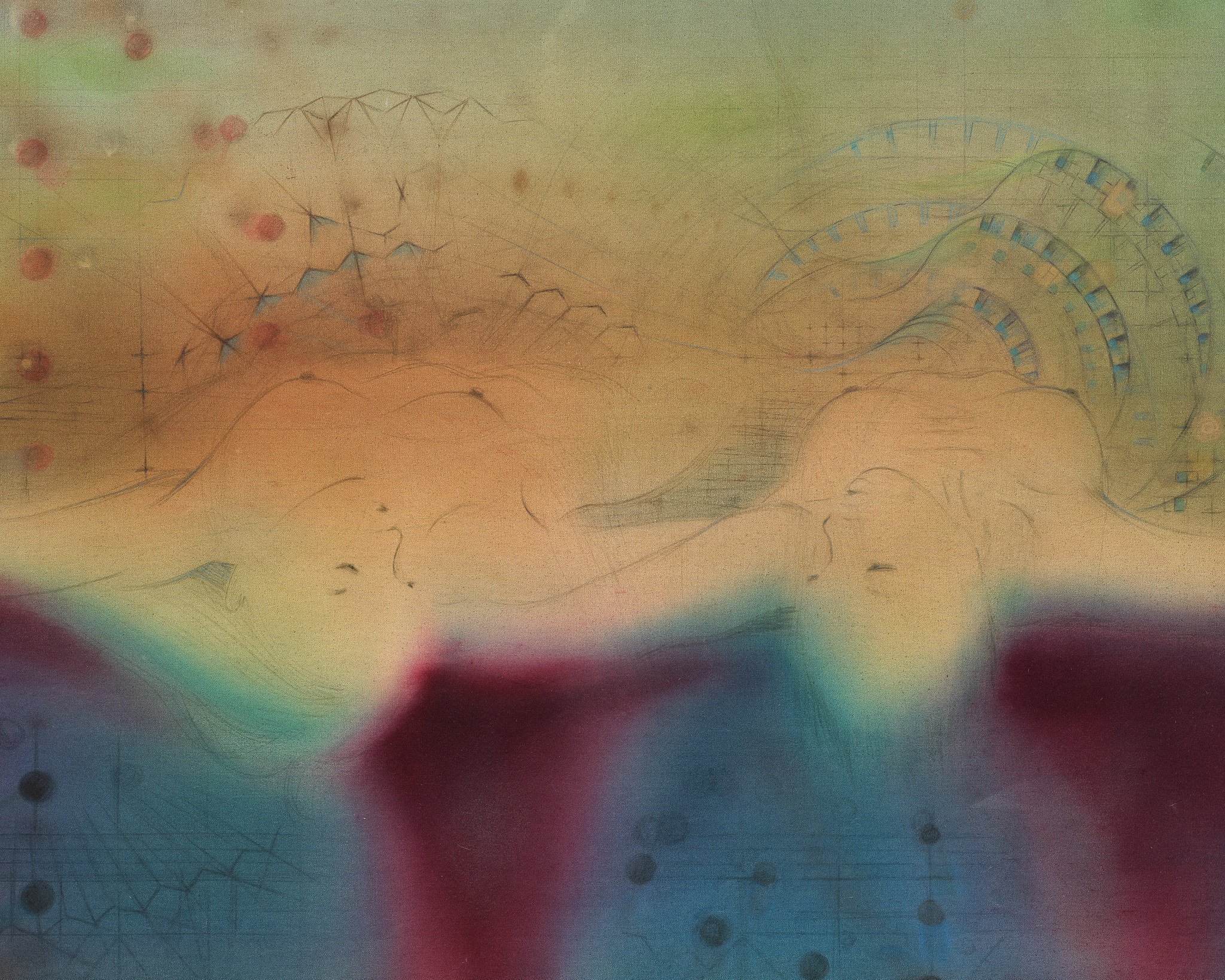

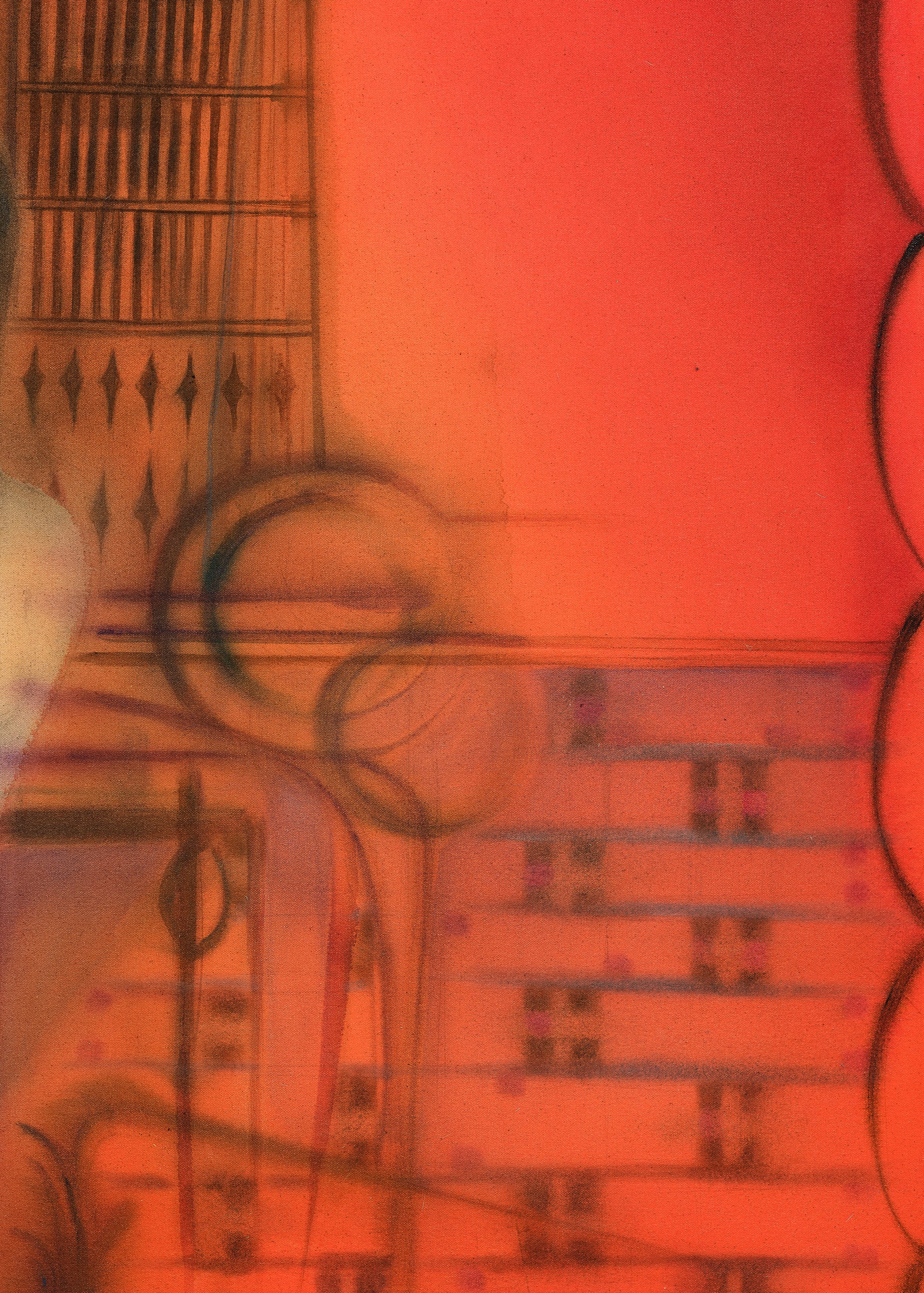

It was believed in the 17th century that emotion—love, in particular—quite literally warmed the heart, which then produced water vapor to cool itself down, which would then travel to the eyes and expel as tears. In their breathy dreamscapes and pools of silky jewel tones tinged with murky stains, Xingzi Gu’s paintings materialize a soft, psychically charged atmosphere in which emotional experience is also physical, akin to “heart vapor.”

The misty sensibility that wells up in Pure Heart Hall, as it does so much of our lives as a source of grief, ultimately lends itself to what the artist describes as a self-generated belief system—one comprised of magically elusive properties of connection and the deeply felt alchemy of relationships that meet us where we are. Here, lightly summarized figures with unfinished limbs and wispy expressions slip in and out of odd moments of gathering and solitude, cuddling and masturbating, disassociating yet substantially present. Through their ethereal motifs of veiling and blurring, Gu obscures clarity of vision like eyes brimming with liquid, smearing distress into love into heartbreak into belonging into free-fall.

In the 2008 novel, Binu and the Great Wall: The Myth of Meng, Su Tong (a touchstone of sentimentality for the artist) imagines a village where it is outright forbidden to cry:

Village women, in an impassioned attempt to hold their heads up in the company of others, sought the ministrations of sorcerers, and most of the clever women had command of the proper magic to prevent crying: they fed their infants mother’s milk and juice of wolf berry and mulberry; when the recipients of this red liquid were fully fed, they fell into a long and peaceful sleep.

This kind of viscous mysticism and ecstatic color, in Gu’s hands, disperses doctrines of emotion governing our private lives—the overdetermined “love” of moral codes, nation states, nuclear families—into airbrushed and runny washes aglow with visceral affect.

What does it feel like to touch the distance and romance of a couple entwined, disconnection within a cherished friendship, or electricity of new recognition in a stranger, across a room and various synapses? Aren’t these narratives of indeterminacy among the most human experiences, of all? There’s no such thing as purity here. As Gu’s characters reach, double, tangle, and merge with one another and their surroundings, they are imbued with freedom to simply not cohere. The resulting paintings are not bound by symbolic allusion, but rather, unfold in a sweet and melancholic search for something to grasp onto: something as formless as we are ourselves in the states of intimacy that hold us together, however unshaped and uncertain.

—Margaret Kross, April 2024.