heaven above sea below

July 30, 2022–September 11, 2022

Reception: Saturday July 30, 6–9pm

Ryan Foerster, Aramis Gutierrez, Van Hanos, Stefan Hoza, Edward Kienholz, David Muenzer, Sydney Shen, Michelle Uckotter

organized by Reilly Davidson & Jacques Louis Vidal

“One is inside

then outside what one has been inside One feels empty

because there is nothing inside oneself One tries to get inside oneself

that inside of the outside

that one was once inside

once one tries to get oneself inside what one is outside:

to eat and to be eaten

to have the outside inside and to be inside the outside”

– R. D. Laing, Knots

This is an attempt to puncture undoingness… teetering between form and function, space and nonspace… disintegrating concepts and stuffs… in heaven there are no bodies, in the sea it's all part of a single body: water.

*

Michelle Uckotter’s abject spatial framework lends itself to the dissolution of self in a space that is, itself, falling apart. One meets her characters on their way into cavernous attics and squalid stairwells. A wanton disposition characterizes this cast of girls as they wander and cavort in destitution or enact violent passions. Hobby horse side steps Uckotter’s standard representation of skirt-clad women. Instead, a rocking horse is found lodged behind a gap in the architecture. On one side a jumble of violet and lavender operates at the fore of a quilted abstraction which reads as a sibling to Kirkeby’s geological compositions. To the left, a similar patchwork lies just beyond distorted wooden planks. The contrast between a preserved child’s toy and an entropic structure attunes one to opposite nodes of being. Is the horse condemned to the nature of its context?

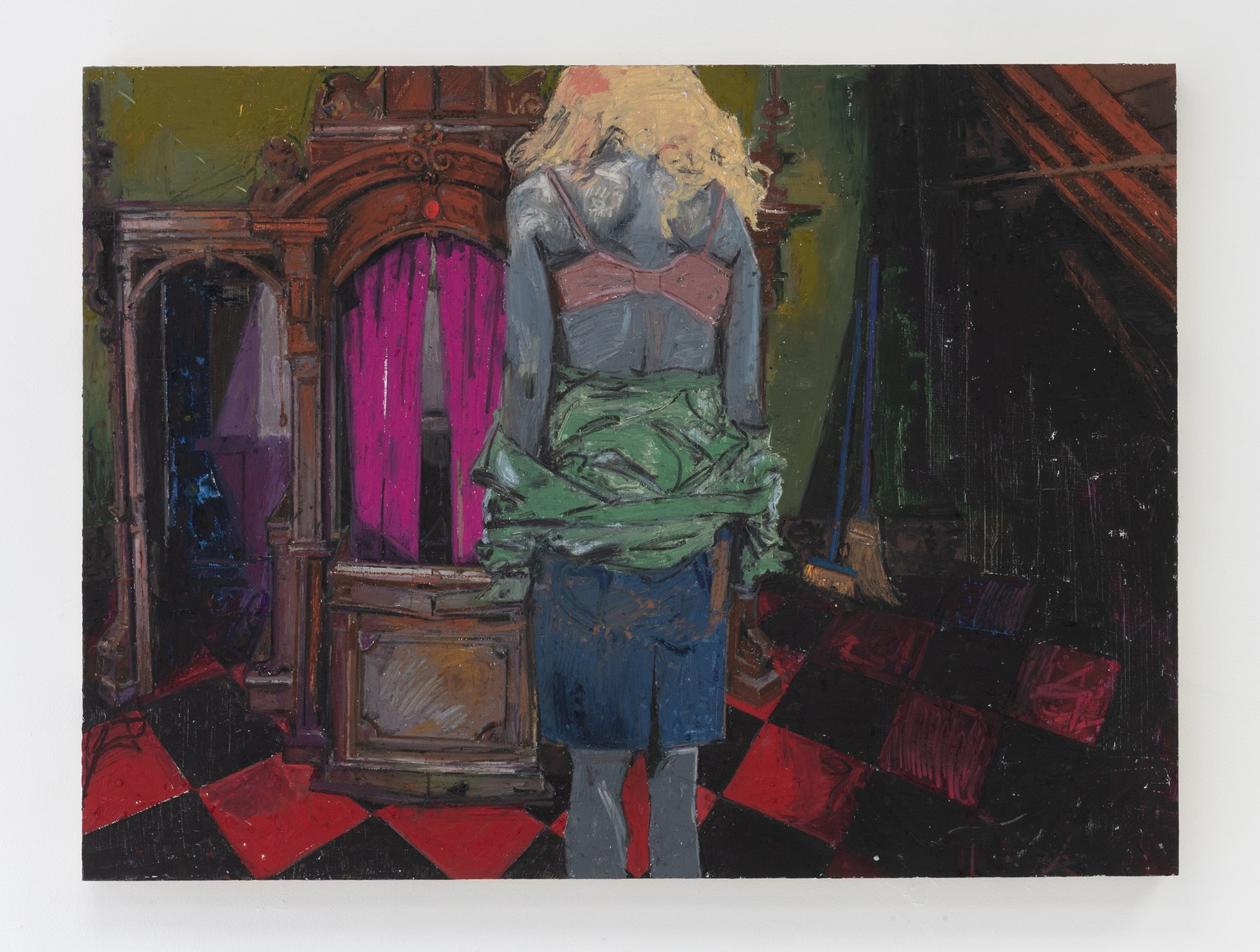

Honest girl with confession booth alternatively elects one of the painter’s attic girls to explore an abysmal interior. Here Uckotter flexes a compositional aptitude as the subject’s flaxen hair and jean shorts invert colors from a pair of brooms nestled in the garret’s shadowy nook. Uckotter’s setting effectively toes the line between thin preservation and complete deterioration. Our lone girl faces away from the viewer and toward a confessionary adorned with fuschia curtains. A cinematic aspect occurs here, eliciting a sense that this is merely one frame culled from a larger plot. The viewer is thus tasked with fabricating dubious answers from sparse details.

*

The back room hosts Stefan Hoza’s “Laughers” series. The set of three finds its genesis in a passage from René Daumal’s essay titled, "Pataphysics and the Revelation of Laughter" wherein he contends that a certain form of laughter carries opposing hubs of human emotion. Here he writes “Pataphysical laughter is the keen awareness of a duality both absurd and undeniable. In this sense it is the one human expression of the identity of opposites (and, what is remarkable, in a universal language).” A destabilizing humor emanates from Hoza’s depictions of jester-like subjects, sparking impressions of shame and discomfort upon the viewer. He works to express the possibility of meaning and dissolution of figures in a series of primary colored oil paintings.

With each image, a general recurring form is depicted with Hoza’s elaborations and new pictorial elements. The particulars in these three compositions oscillate in legibility. A cartoonish eye appears on a blue laugher and is reincarnated as a haunting red orifice on the other. His “Laughers” are consistently snide, apparently sneering at those who meet them. The figures are caught somewhere between the aesthetics of Picasso and Picabia. Daumal goes on to insist that pataphysical laughter could also signify “the subject’s headlong rush toward its opposite object and at the same time the submission of that act of love to an inconceivable and cruelly felt law which prevents me from achieving total and immediate self-realization–the submission, that is, to that law of becoming according to which laughter is begotten in its dialectical forward march.” This is the march Hoza is compelled by, one plagued with contradiction and fluctuating semantics.

*

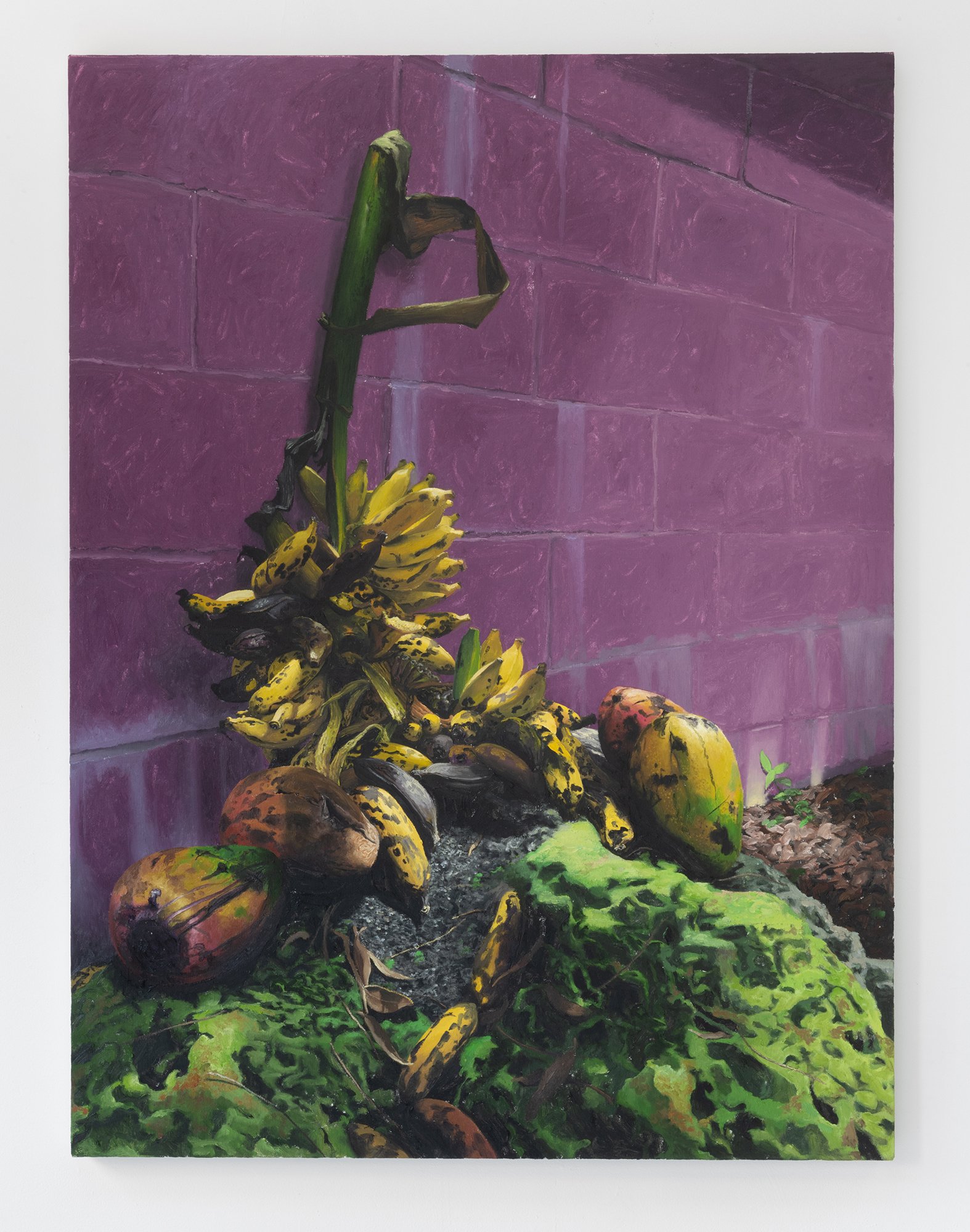

Hanging in the mainspace are two allied depictions of banana stalks in variable states of decay. Aramis Gutierrez provides snapshots of yellow fruits mid and post ripening. His paintings are prescient, inflicting the feeling that one could almost reach beyond the canvas’s surface and clutch its fabricated contents. Gutierrez’s Miami context is critical for the understanding of the banana tableaus as spiritual encounters and gestures of reciprocality. In the city it is common to discover makeshift Santería or Voodoo offerings and altars in largely forgotten locales. Whether clustered in a parking lot or the back of a building, these assemblages are fashioned in order to placate various entities.

Recent brushes with death also provide Gutierrez with an intimate connection to the realm beyond a material one. He illuminates a conduit’s endeavor as a companion to his portraiture. In a series recently exhibited at Miami’s CENTRAL FINE, Gutierrez explores orgyistic vignettes of friends cavorting in dense vegetation and saturated domestic spaces. One banana tableau appears in Banana Ester & Petrichor, attuning viewers to the frequencies between people and their aggregates.

*

Stationed on the gallery floor, Sydney Shen’s haystack furniture is arranged so that one may sit and contemplate the paintings on view while feeling the acute poke of rogue straws. This work is stimulated by her consideration of idyllism, barn weddings, haunted hay rides, and the kitsch-cottage sensibility at play in Target’s Magnolia brand and Michael’s craft store. She remixes temporalities and semiotics in a meticulous fashion. Shen’s furnishing is also condemned to an undoing. Straw will inevitably scatter about on the gallery floor as visitors interact with the arcadian sofa.

Shen fixates on concepts, navigating their depths in search of full comprehension. In an interview with Xin Wang, she details this process, expressing that “It’s definitely difficult to prioritize which ideas are worth following down the rabbit hole. The novelty of something might make it interesting at first, which leads to a hyper-focus, only for me to later realize that I didn’t want to work with it at all.” With this installation she affirms one of her interests by returning to a versant frame of reference - that of pastoral fantasy.

*

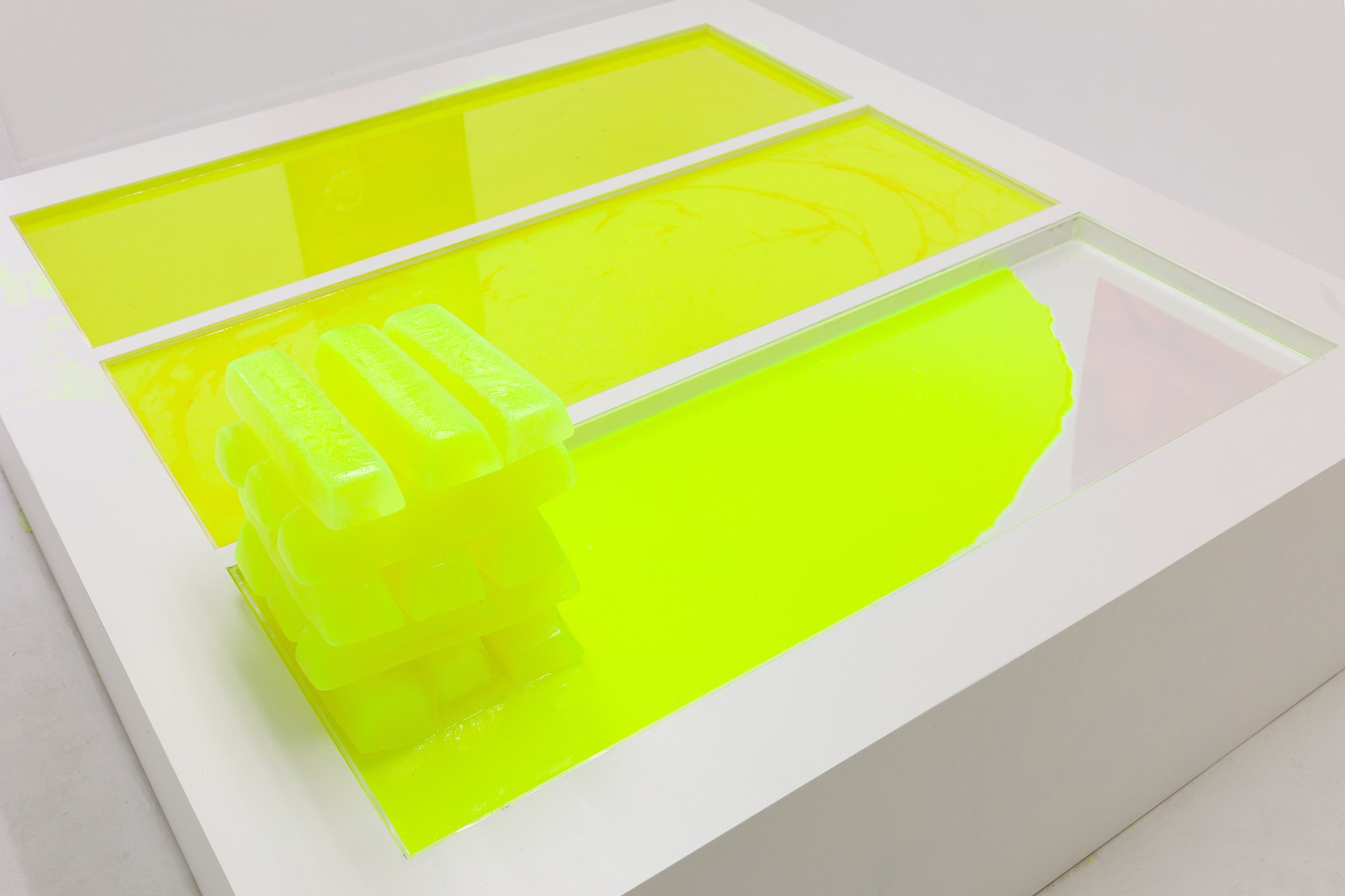

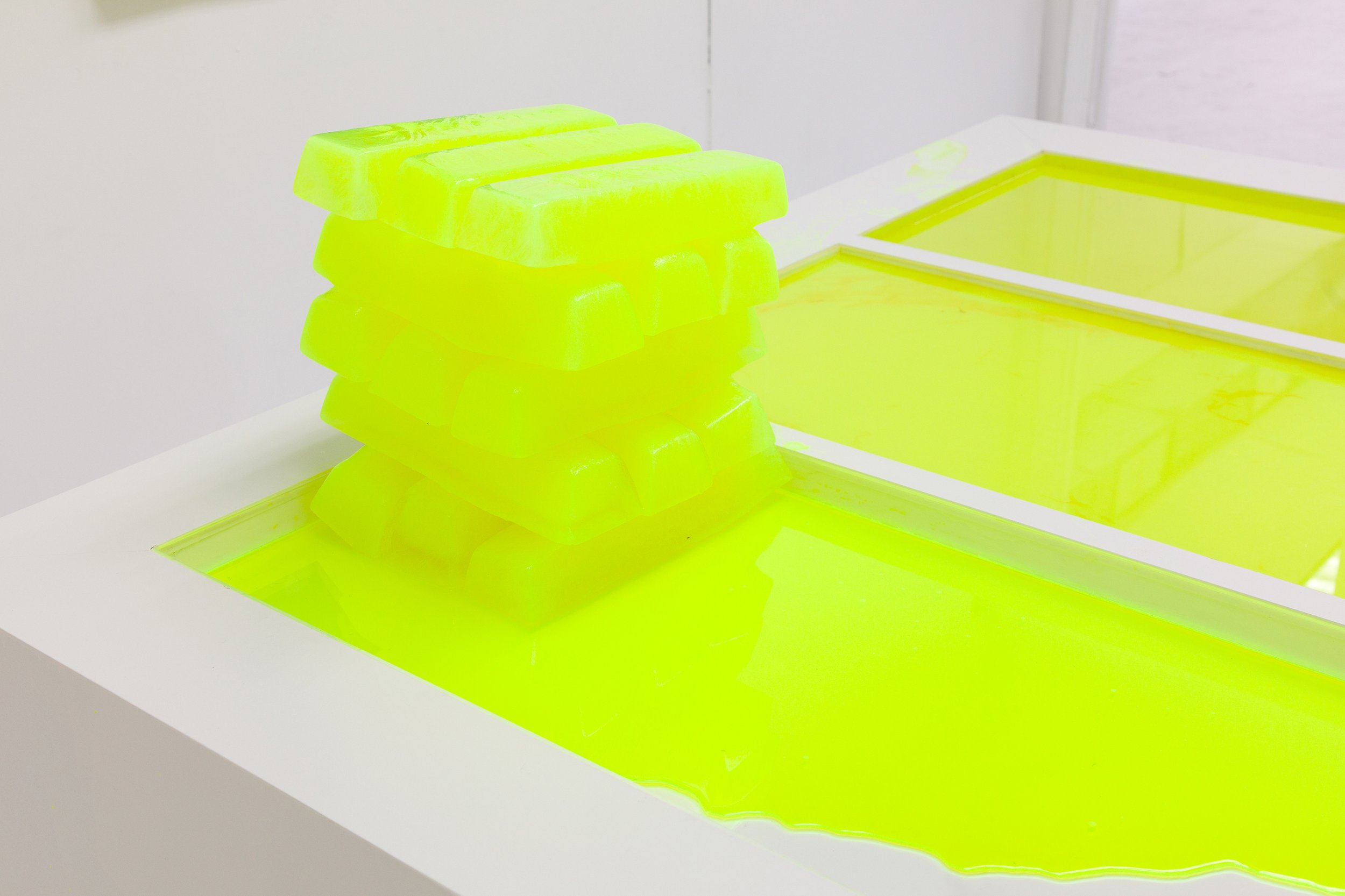

David Muenzer also articulates a certain experience of elapsed time by way of melting highlighter ink. Staged in intervals, three basins provide space for the frozen yellow bricks to melt in response to the gallery’s well above freezing temperature. First staged for the 2016 exhibition Scalar-Dameon at Reserve Ames in Los Angeles, a new setting and a new material inventory crafted in downtown New York revives an idea borne from the desire to test the process quantification. The tri-phase development of Muenzer’s situation precludes the possibility that this event could occur anywhere but here and now, as the ingots’s manner of unfreezing is directly contingent upon the space’s precise climate.

Alongside the ingot trays, Muenzer contributes one of his signature red globe figures crouched atop wooden railings. Solo IV’s protagonist mirrors the foreboding demon’s posture in Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare. Under Muenzer’s direction however, the viewer’s perspective comes from below. One observes the character in a specific moment - will he jump or is he settled in his vigilant disposition? The potential here implies danger, a calm before the storm. Returning to Picabia, a particular musing strikes a chord here: “Our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction.” Muenzer takes this to the extreme, as his sphere-headed figures denote a literal “worldliness” per shape and design.

*

Edward Kienholz injected objects with new use-value, his Americana sensibility merging with a knack for assemblage. The self-taught sculptor invoked his experiences in construction, metalwork, and auto repair to combine found objects and offer new monuments. The metal cans here are embellished with soldered fixings, antennae, and hand-applied epoxy resin. Inside, he’s lodged Fresnel lenses which give the sculptures the chance to emanate a transfixing glow. These materials are resuscitated as magic objects.

In a 1990 interview for NHK, Kienholz explains that his sculptures were made in order to "unpleasant or unacceptable parts of society," furthermore, "as a way to start a dialogue, a conversation [...] that could reach some people.” A certain optimism is injected here, as Kienholz notes his work could lead viewers to “think of the way they are spending their very very limited time on earth. Maybe they could do it better." Pushing past disillusionment and bearing violent material witness to the conceits of a throw-away society.

*

Ryan Foerster, another master of detritus, revives begotten objects. Despite a Canadian upbringing, his work implicates a resoundingly American penchant for excess. He assumes the roles of scavenger and conservator, collecting rubbish from the shores of Brighton Beach and piss-fumed alleyways of New York City. These recycled materials expand in utility, combined as art-objects in opposition to their previous fates as decaying relics. To this end, Foerster contends that “I think composting is a really good metaphor for my work—the entire cycle where old work generates new work—it’s the in-between stage where discarded food gets turned into a rich soil again to grow more food.”

Foerster’s orange C-print reads as a distorted I Spy where various dinosaurs and spoons are scattered amongst other random ephemera. Several Fruit of the Loom briefs are burdened with nagging objects - mainly seashells. His body of work bears traces of decay, as if it was assembled in the wake of a tempestuous storm. Beauty appears as if by mistake, chance and processes of degradation inevitably dictating Foerster’s outcomes.

*

Van Hanos displays his expertise by flitting between styles, consistently evading identification with any singular compositional identity. Instead, the painter excels at commanding his medium with a dexterous conviction. He delivers a massive oeuvre of painterly inflections, meandering between formal conceits and rejecting artistic conventionality. The implacability of his work scorns an art world precept that one’s work needs a signature style. Hanos divests ego by frustrating authorship. Though heterogenous in style, the hold these works take on the viewer is miraculously consistent. This is where Hanos flourishes, in the commitment to affect despite his dissolved boundaries. There are many cooks in this kitchen, Hanos embodies each and every one of them.

While Hanos takes an appropriative stance on the increasing solubility of images, there are portals in his paintings which allow the viewer to parse his brandless mode of creation. He takes steps backward and forward, enjoying the impermanence of a mark. During the process, he glides between painter/meditator, editor, and director, in the end assuming all three positions. In particular, Still life with flare and fly takes the tradition of Dutch still life painting as its referent, likewise incorporating vanitas motifs such as small fly and a flare of light. Hanos has assembled these objects twice now, depicting the configurations accordingly. Meaning is piecemeal: drumsticks he learned on, refuse from an old sculpture, a curved dolphin rib becomes a relic. Hanos expresses his stance on painting as “an empty vessel that you fill” and “a glimpse into a life” where one can “account for what happened.”

*

“But this is not enough. One is trying to get

the inside of what one is outside inside, and to

get inside the outside. But one does not get

inside the outside by getting the outside inside

for;

although one is full inside of the inside of the outside

one is on the outside of one's own inside

and by getting inside the outside

one remains empty because

while one is on the inside

even the inside of the outside is outside

and inside oneself there is still nothing

There has never been anything else

and there never will be”

– R. D. Laing, Knots

Thank you.

– Reilly Davidson