Frieze New York 2022

May 18–22, 2022

The Shed

545 W 30th St

New York, NY 10001

Press

ArtNews: Marsha Pels’s Sculptures About Loss Stun at Frieze’s Section for Young Galleries

Artsy: What Sold at Frieze New York 2022

Frieze: Sculpture From $10K - $1M on Frieze Viewing Room

The New York Times: At the Shed, Frieze II Takes Off

Time Out: 11 interesting works to catch at Frieze Art Fair this weekend

Frieze: Marsha Pels: ‘If I don’t transform an object, it doesn’t work’

Financial Times: Frieze Frame’s Sophie Mörner: ‘I don’t like being comparmentalized’

Frieze: Emerging Art from Taipei to Tehran: Frame at Frieze New York 2022

Marsha Pels

The Shed

545 W 30th St

New York, NY 10001

Wednesday Preview, May 18 (invitation only): 11am – 7pm

Thursday Preview, May 19 – Saturday, May 21: 11am – 7pm

Sunday, May 22: 11am – 5pm

In her first presentation for Frieze, Marsha Pels evokes the Surrealist lineage of the “Exquisite Corpse” in four wrenching sculptures. Like the parlor game of chance, she juxtaposes unexpected materials, disparate styles, and idiosyncratic techniques, resulting in darkly comic amalgamations held together by a kind of irrational logic. Deploying the uncanny is not only, however, a formal conceit. The works are themselves macabre: skeletons, cadavers, ghosts, and anatomical anomalies narrating more than a decade of personal and civic ravages.

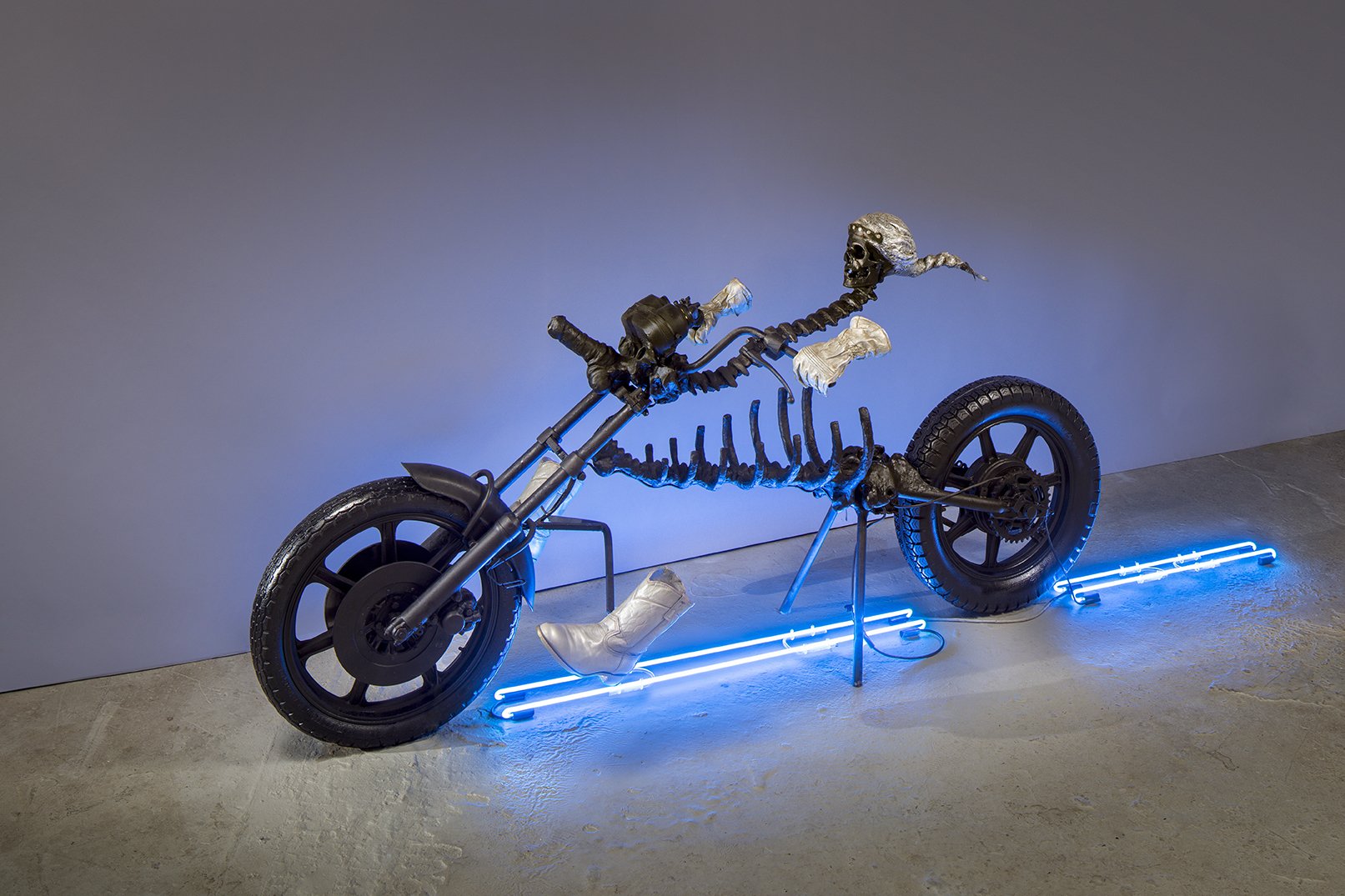

Pels frequently works autobiographically. Two works appear here from the series “Dead Mother, Dead Cowboy” (2006–08), monuments to loss. Following her mother’s death — and a lifelong difficult relationship — the biting Écorché (2006) affixes twenty casts of Pels’s hands and arms, wearing her mother’s satin gloves, inside her mother’s mink coat. Her cast hands are stacked, smallest to biggest, like a rib cage, buffeting an absent spinal column. (Écorché, French for “flayed,” is a technique of representing human anatomy without skin.) Pels then made Dead Cowboy (2008), after her former partner left her unexpectedly; a portrait of a fossil in motion, a ghostly macho remainder, of swagger turned sinister.

Self-Portrait, Detroit (2010) materializes another specter, the artist herself, as a faceless spine encased in a replica of Detroit’s Central Terminal train station and hovering over a pile of illuminated carnage. Healing from a painful neck surgery while living in Detroit, she described both her physical state and that of the city as “broken-down and immobilized.” Finally, Pels’s Chatelaine of Eviction (2014) suggests yet one more body, the would-be wearer of a set of keychains attached to a waistbelt. (“Châtelaine” literally translates to “Lady of the Castle.”) Pels instead fashions a chatelaine dripping with the violent tools of construction she saw in her gentrifying New York neighborhood. In cast aluminum, these metal cranes and bulldozers look like guns.

Though indebted to Surrealism’s inexplicable beauty and convulsive encounters, Pels’s exquisite corpses leave little up to chance. Her practice is proof of control, of clarity, and of mastery. She handles her materials with virtuosic confidence, moving between wax, metal, synthetics, plaster, crystal and found objects that she alchemizes through casting, welding, and patination. She collides a wide range of influences including Renaissance anatomical studies, Victorian jewelry, and Arte Povera. Through the many collaged layers of reference, of research, of process, and of transformation, the governing (il)logic of Pels’s work is, in the end, Pels herself—all she has haunted and that haunts her in return. Reality is often stranger than fiction.

— Sara Softness, May 2022