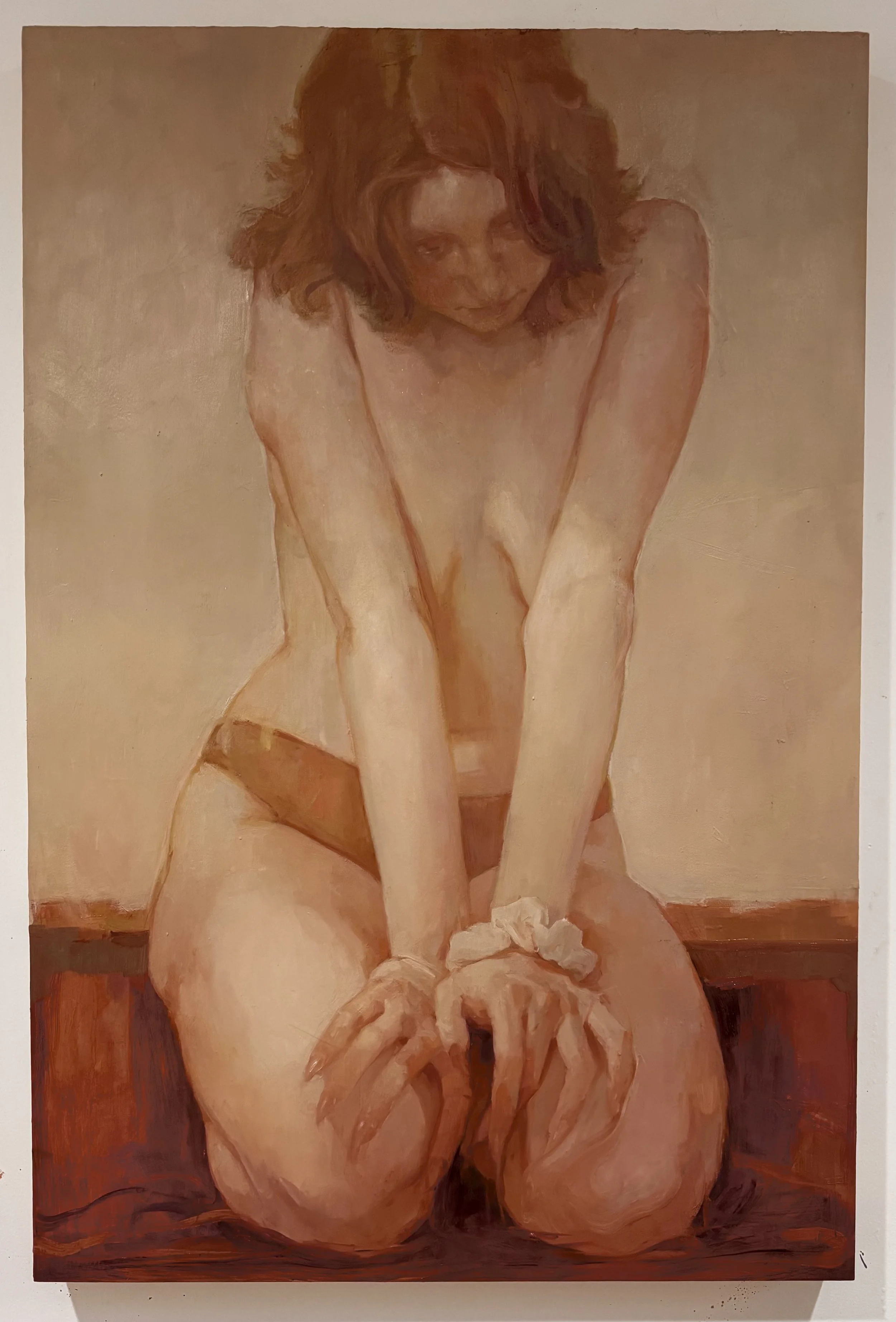

Flesh is the Reason

September 6, 2025–October 5, 2025

Reception: Saturday September 6, 6–10pm

Gretchen Adel, Ophelia Arc, Brenda Barrios, Ben Cowan, Lily Hyon, Wen Liu, Madeline Owen, Alina Puccio, Josh Rabineau, Carson Rauschenberg, Noah Trapolino, Kirsten Valentine

organized by Shirley Lai & Noah Trapolino

Flesh is the reason oil painting was invented

—Willem de Kooning, 1952

Willem de Kooning could have used a number of words to frame his now infamous line on the reason for oil painting being created: body, skin, form, figure… yet he chose “flesh”. Flesh has an important history that De Kooning, knowingly or not, rightfully invokes. Dating as far back as the 3rd century AD, Flesh was used to construct a specific, new, and apocalyptic understanding of the world of Sin as it pertained to the rise of Christianity. For these early theologians, Flesh is the “matter” which has been corrupted by Sin, a corruption which we can only be saved from by a sacrifice—that of Jesus Christ. How this “sacrifice” actually saves us is hotly debated at the time: does it cleanse us like ancient purification rituals? Is it a purchase on God’s part to trade our bondage to Satan over to a bondage to God? Is it a symbolic renunciation of the body in favor of the spiritual? Whatever the case, each mechanism for salvation hinges upon the status of the Flesh.

It was the serpent who suggested the first sin, Eve representing the flesh was delighted by it, and Adam representing the spirit consented to it.

–Gregory the Great, 595 AD

For the Apostle Paul, Sin had become so enmeshed with Flesh that “Flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God” (1 Cor 15.50). Origen, arguably one of the most influential theologians, saw Flesh as “good”—Flesh was an aid to salvation—the medium through which we attain spiritual redemption. For Augustine, the soul was joined with the Flesh—God chose to make them combined. But Augustine, despite his acceptance of the Flesh, had to contend with the “morbid condition” of desire, lust, and the involuntary erection. Augustine had to conceptualize Sex Without Sin. Control over the body—the involuntary erection as symptomatic of lack of control over Flesh—a state of fallenness. The Orgasm as “Shame-Producing-Pleasure”. It is here we now can turn to art and our show.

What moves a person is not what she knows, but what she wants

Flesh is the Reason, not just for oil painting's ultimate use or for theological anxieties, but also for our current political climate: whose flesh is allowed to be desirable? Who deserves flesh? What do you do about the flesh you don’t desire? That Augustine has to dream of non-shameful sex is just the beginning of a legacy that haunts us: an uncertainty over our own sources of pleasure. Flesh is always contested, not just amongst people but also within themselves. Art operates at a unique crossroads of desire and politics—to represent the unrepresentable sensations associated with flesh—the experience of seeing a body that De Kooning rightfully put oil on top of. What is evoked when you gaze upon a nude form? A naked figure? When the girl stares down at you, the man spreads his legs, when Jesus himself is opened up to you on the cross—do you feel ashamed? Or are you excited?

Our Eroticism is not new: it is a necessary reminder, reclaiming, and recapitulating of the body as a site of politics. A reminder that the body is in flux—who is claiming it? Whose body gets to be desired? A reclaiming of the libidinal charges associated with the body—a rejection of Gooning, of utilitarian, sadistic Pornography in favor of A Tempo of Intimacy, of an excess sacrificed, a Masochistic Eroticism. A recapitulation—in a different space, a different audience, and a different visual collaboration of our collective desires.

—Noah Trapolino, September 2025

The flesh tells a story. When we look at a nude body of an artwork, maybe we feel a twinge of shyness or admiration, informed by the expression of the face, the posture of the body, or the color palette on the canvas. The Body depicted in art, when done well, can trigger affects and sensations in us that many other representational art forms cannot. It is both a tragedy and miracle of the human experience that pursuing requires one to put themselves at the mercy of another: devastating rejection or complete acceptance. How useless the fear of intimacy is in enacting the unrealized pain to suffer a false reality, and how foolish it is to harbor hopeful expectations to dream of safety in a trap that we willingly set for ourselves. Such is the human condition, as well as our ability to avoid this perceived danger. In the same way in which we bare our skin, revealing an earnest truth makes one feel naked. Every bid for connection, every effort, every desire, is a risk to lose or gain.

With the imbalanced emphasis on an individualistic approach to careers and family building over connection and community, our bandwidth to hold space for others becomes limited. We have cultivated a breeding ground of emotional unavailability and fear of intimacy. Loneliness is as pervasive as ever. Capitalism and advanced technology has enabled society to commercialize and repackage intimacy into false digestible portions. We turn to porn, hookup culture, social media likes, to inject the dopamine that a lack of human connection has left a void for. With the pressure of constant self surveillance and self management, becoming attractive or perceived as attractive becomes the end, rather than the means to an end. These strategies of coping allow us to straddle the avoidance of both intimacy and loneliness, and throw money and efforts into the abyss to feign validation in place of disconnection, supplementing our flesh in physical and digital ways to make up for the emotional void. Real intimacy is so rare and inconvenient to us that we must resort to these corporeal manifestations.

Flesh is the Reason acknowledges the horror of flesh itself as a direct metaphor for the horror of intimacy and connection—at once dangerous, infection prone, disease ridden—yet also soft, life maintaining, and pure. It embodies the risks taken in pursuit of connection. Erotic imagery takes its power back from sexualized connotations and recontextualizes itself as a sincere exposure. The subject becomes prey to the viewer who has a choice in a sympathetic understanding or objectifying lens. In Wanting: Something Honest, Adel places the yearning figures in colorblocking patterns resembling a digital glitch landscape of the internet, disjointed from reality. Paintings from Owen, Rauschenberg, and Valentine’s emphasize the sensual rather than sexual. The anachronistic scenes of Trapolino’s triptych invites you into the light only to question who is looking back in the shadow. Puccio transforms explicit underage memories into explosions of strokes and colors, even monumentalizing it in Bedroom at Night to question the motives of the subject, the artist, and the viewer.

In other works, the body is torn apart, its organs and limbs extracted, or subjected as an offering or a confession. Symbolically expressing the complexity of sexual desires from shame to detachment, Hyon amputates the fetishized feet from its body, while Cowan performs penectomy and castration on marble sculpture paintings. Arc’s Wo(und)mb study invites the viewer to peer in a womb or wound, adeptly alluding to the great risks and rewards of the flesh. Barrio’s metal copper sculpture, taken from a mold of her own body, disappears into the surface, communicating the existential dreads and hardships that make one want to disappear. Similarly, Liu reinterprets the body as an exoskeleton filled with pink colored resin filled with Chinese herbal medicine inspired by her own treatments in Inarticulate Trace No. 3. Finally, Rabineau’s sculpture carefully reveals authentic selves in controlled glimpses, windows to deep psychological desires and fears.

This collaboration of artists probes the experiential journey to exist as we enter the maze of today’s society, communicating the depths of existence in the bodies they mold. The artworks resonate with the heartfelt efforts it takes to live, yearn, have human desires and needs, and empathically call for earnest and genuine emotional and intimate connections–an invitation to reclaim your flesh and face your fears.

—Shirley Lai, September 2025